It is critical to engage the technical, medical , and (blood bank) nursing staff in this process, That is why it is so important to identify a core of computer-literate users to help with the building and testing/validation.

I don’t mean finding staff who can already program or code. Rather, I mean staff that are astute with knowing their work processes and who had good skills with Microsoft Office and Windows or equivalent. I did not expect them to understand database structure or use structured query language. They were chosen for their ability to learn quickly and their meticulousness.

For our blood bank system, I chose computer-literate technical staff to be involved in the build from the very beginning. They learned how to test each module and to some degree support it. These became my Super-Users and to this day support the system for many tasks. These staff served as the system administrators and worked directly with me as the Division Head for Laboratory Information Systems. They were not full-time and still had their other clinical/technical duties. They liaised with the software vendors engineers.

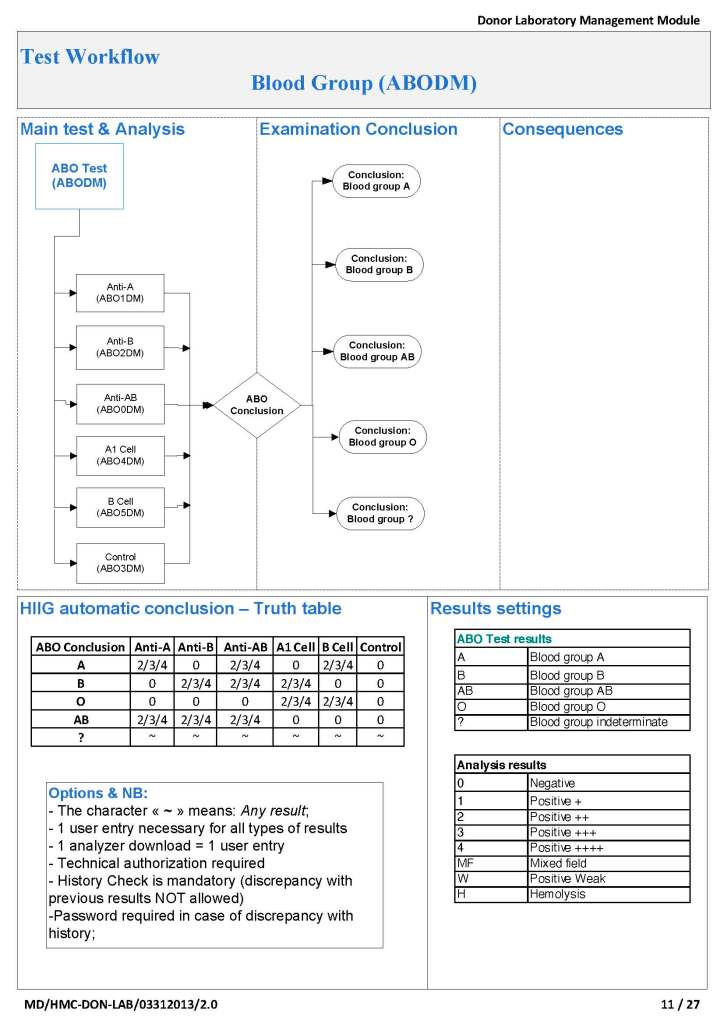

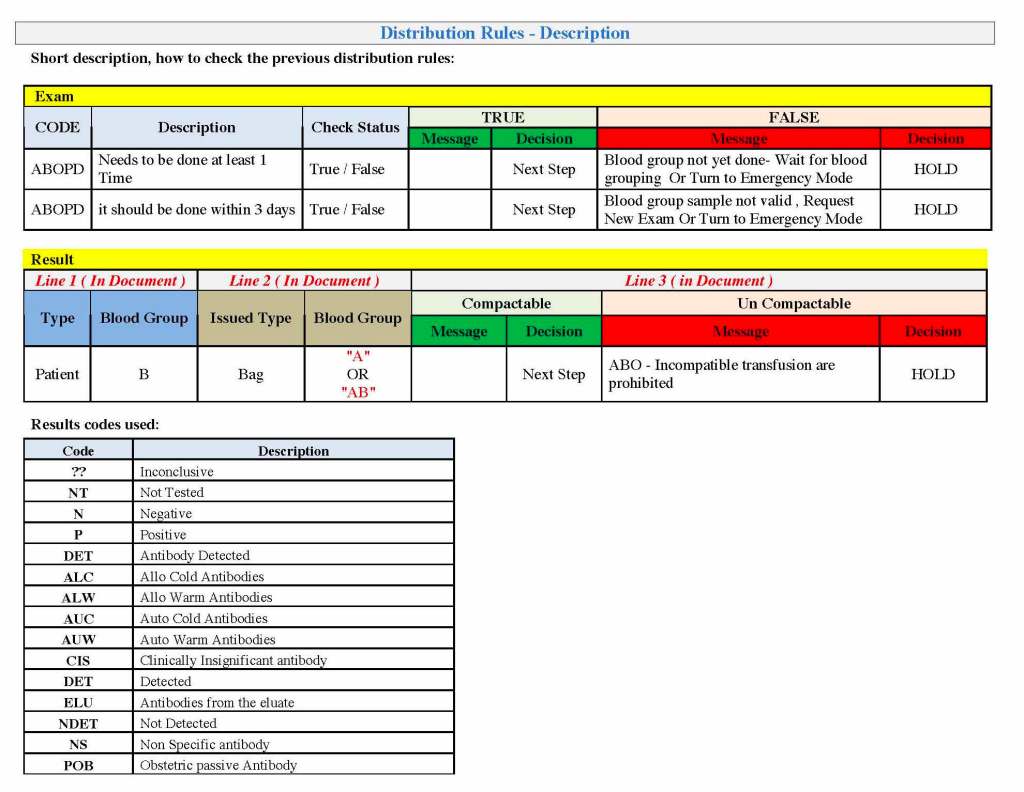

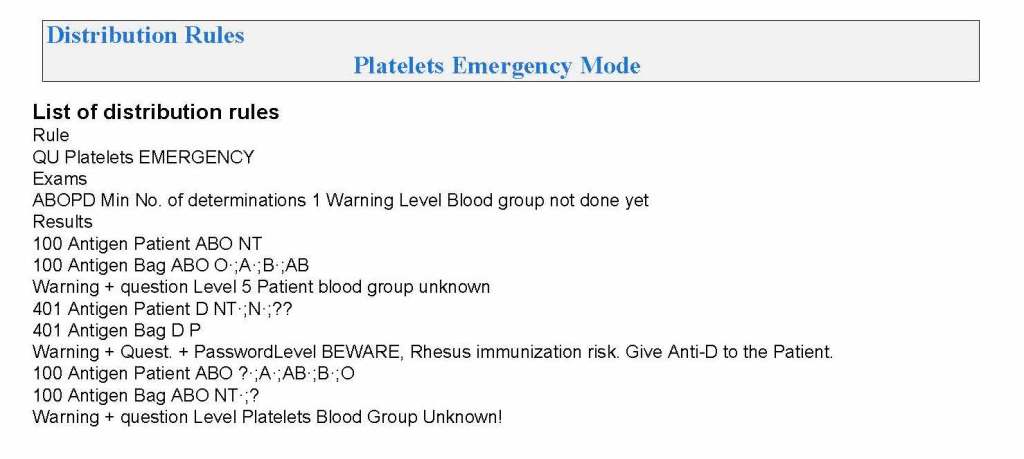

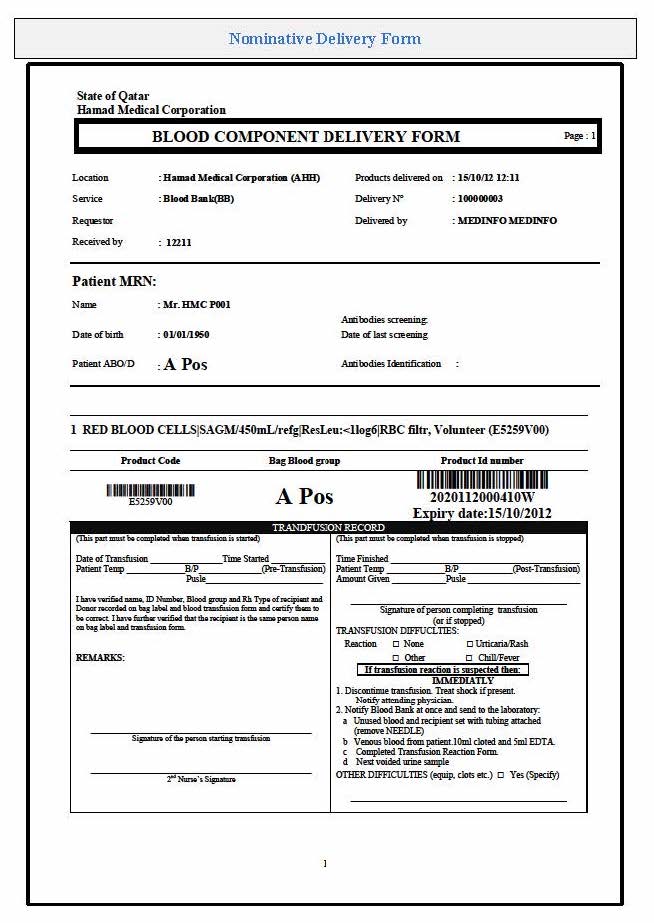

Our blood bank system was NOT a turnkey system. It was custom designed according to our workflows. There were NO default settings!! We had to be remember, ‘Be careful what you ask for, you might get it!’ In some countries, approved systems are turnkey and may allow only few changes to the core structure and thus may not be this optimized for the needed workflow; often only cosmetic changes are permitted.

When we built our first dedicated blood bank computer system, the company would take a module and completely map out the current processes collaboratively with me. After this, I analyzed the critical control points and started to map out the improved computer processes that would take over. After that we would build that those processes in the software and test it. If it failed, we would correct it and test again…and again if necessary. Fortunately, the blood bank vendor did not charge us when we made mistakes.

Sadly, another vendor (non-blood bank), only gave limited opportunities to make settings. If wrong, there might be additional charges to make corrections. This other vendor really pushed the client to accept the default settings regardless whether or not they actually fit. End-users were selected to make and approve the settings, but they were only minimally trained on how to make the settings. It was a journey of the end-users being led to the slaughter—and being blamed for their settings when they accepted the vendor’s recommendations—they usually selected the defaults. There wasn’t enough time for trial and error and correction.

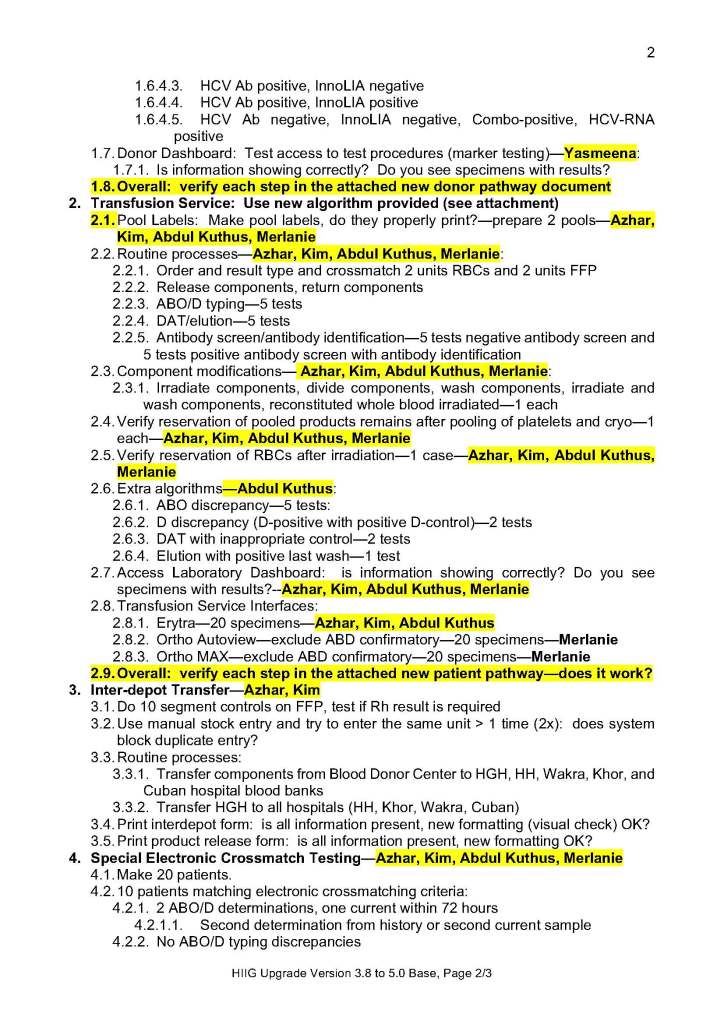

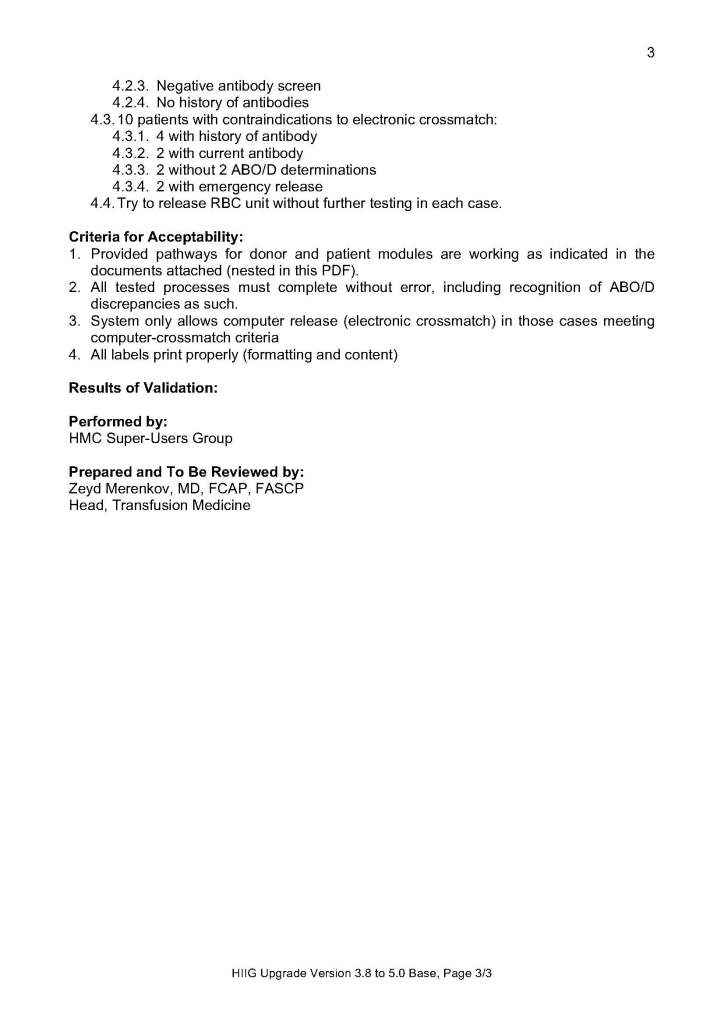

The blood bank system Super Users were an important part of our process. They were an integral part of the implement team and could propose workflows, changes, etc.—subject to my approval. They learned the system from the start and developed invaluable skills that allowed them to support the system after the build. Also, they could serve to validate the system according to the protocols I prepared. Moreover, I took responsibilities for their activities and they were not left out to hang.

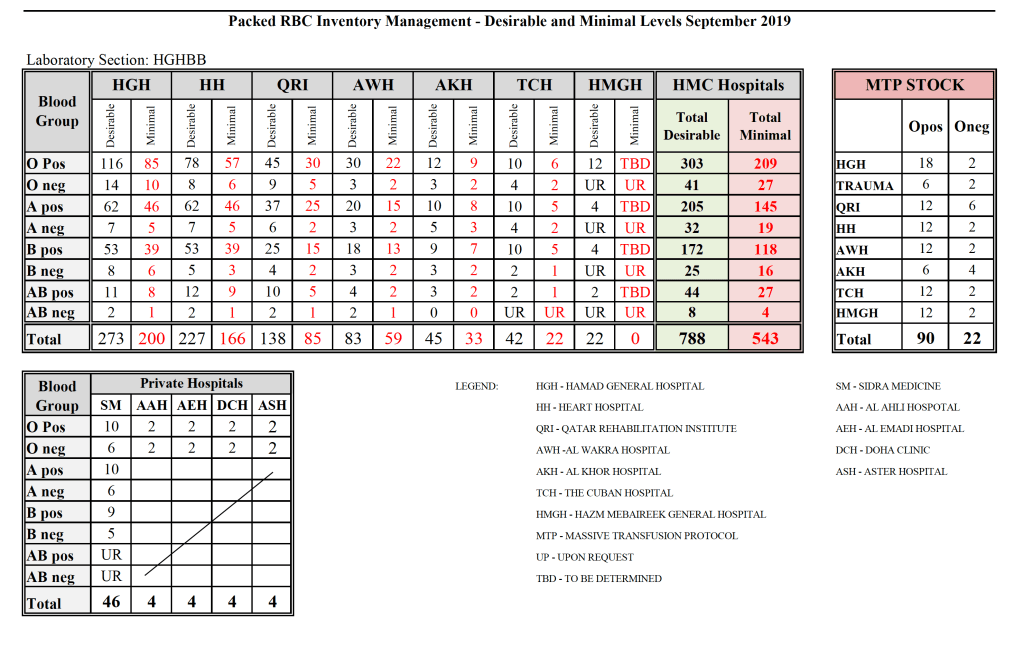

Every hospital blood bank location and the blood donor center had Super-Users. These included:

- Blood Donor Center:

- Administrative Clerk for donor registration, consent, ISBT specimen labels, creation of new donors and patients for validation purposes

- Apheresis/Donor Nurse for donor questionnaire, donor physical examination, and donor collection

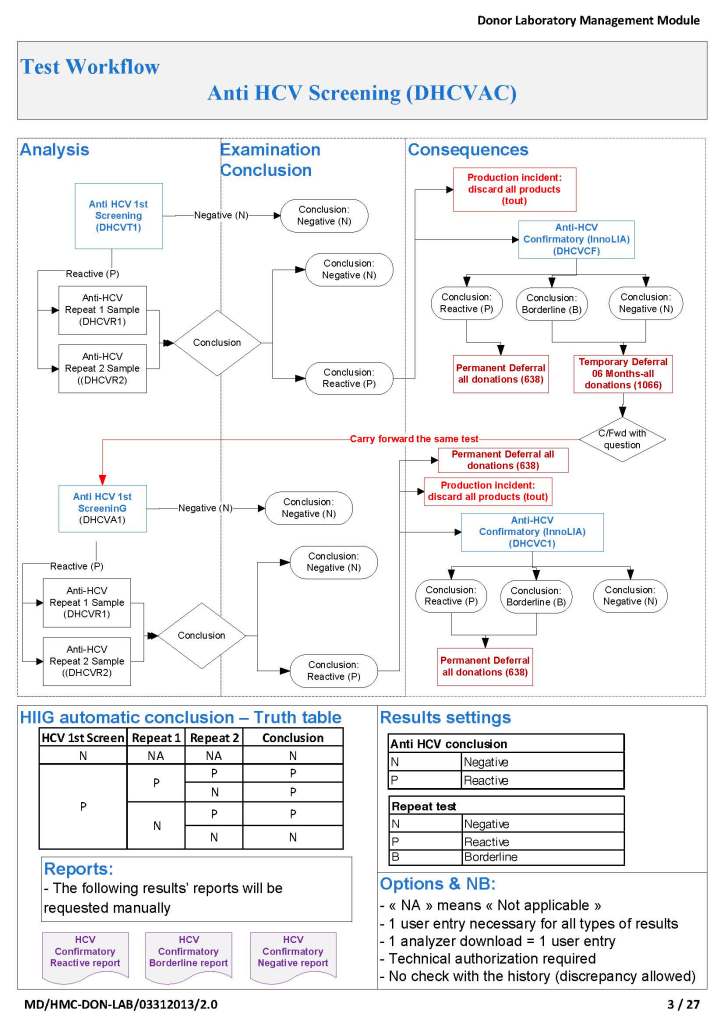

- Medical technologist for donor marker testing

- Medical technologists for blood component production including Reveos, Mirasol, platelet additive solution, pooling, and leukodepletion

- Medical technologist for donor immunohematology testing

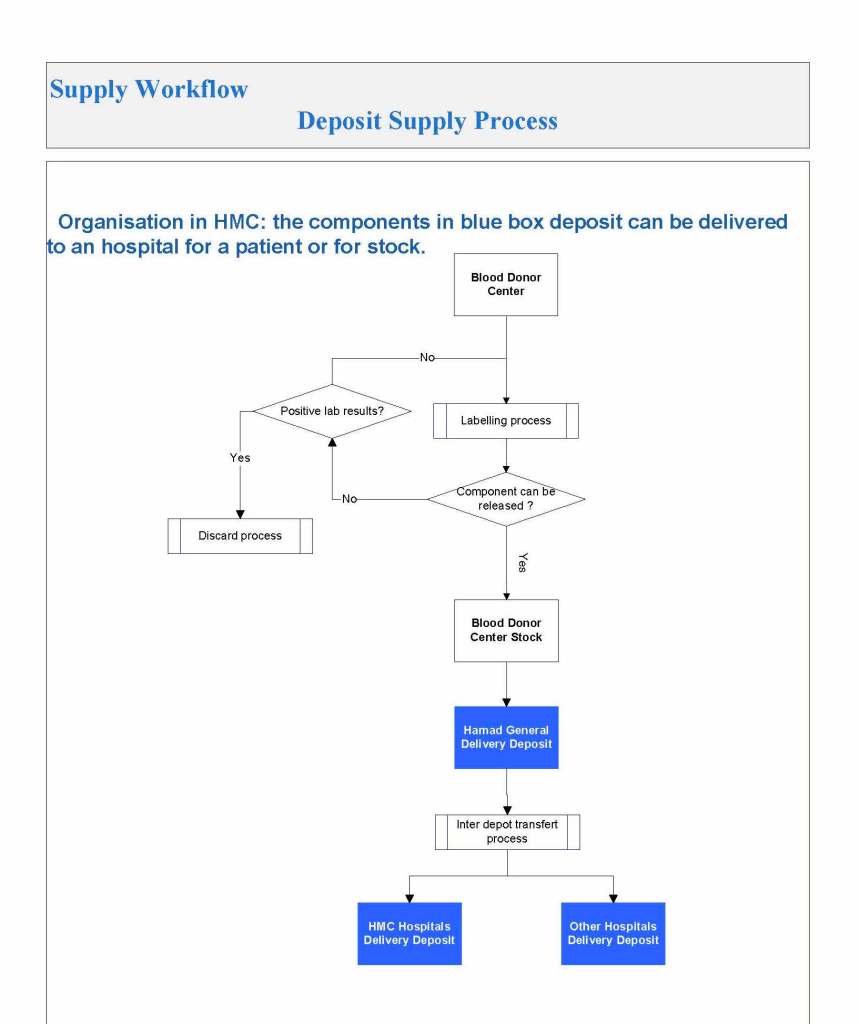

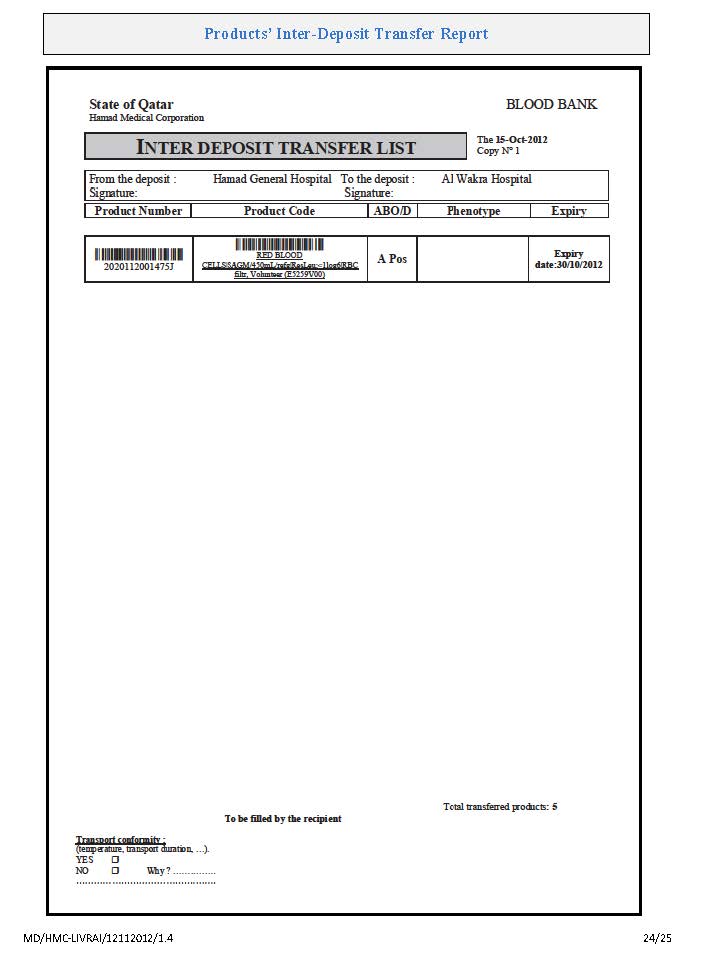

- Medical technologist for inter-depot transfer of blood components

- Hospital Blood Banks and Transfusion Centers:

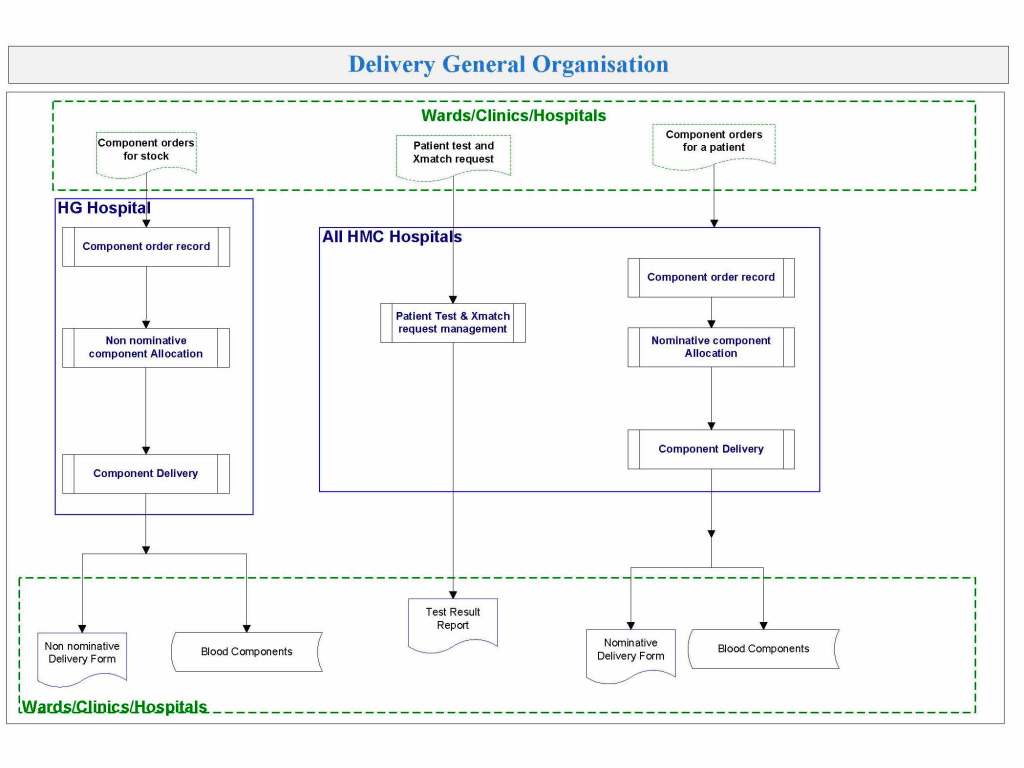

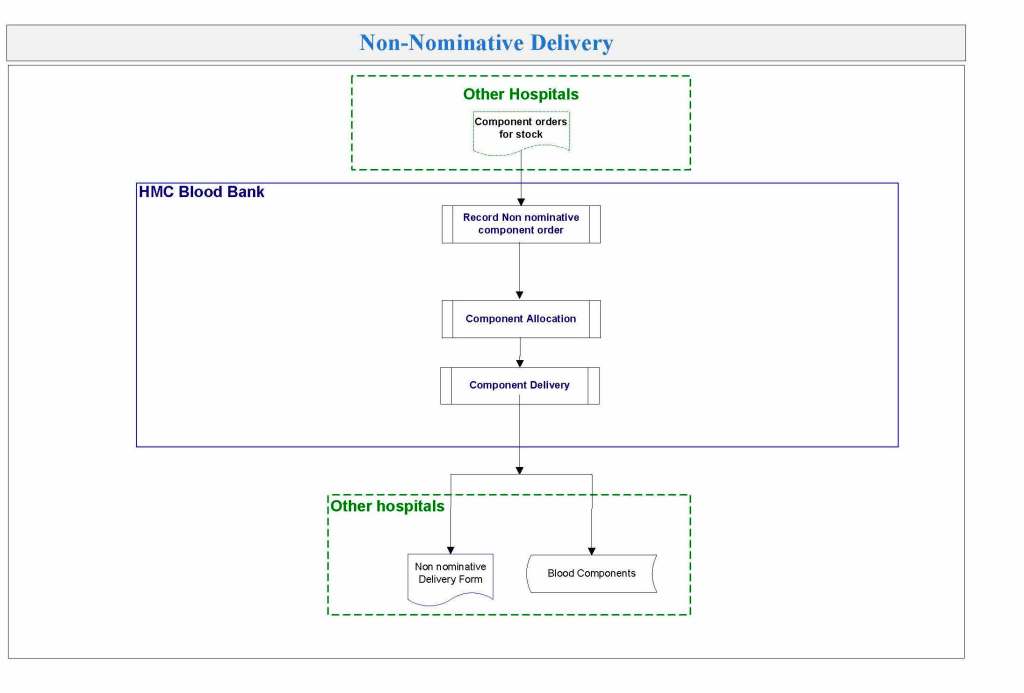

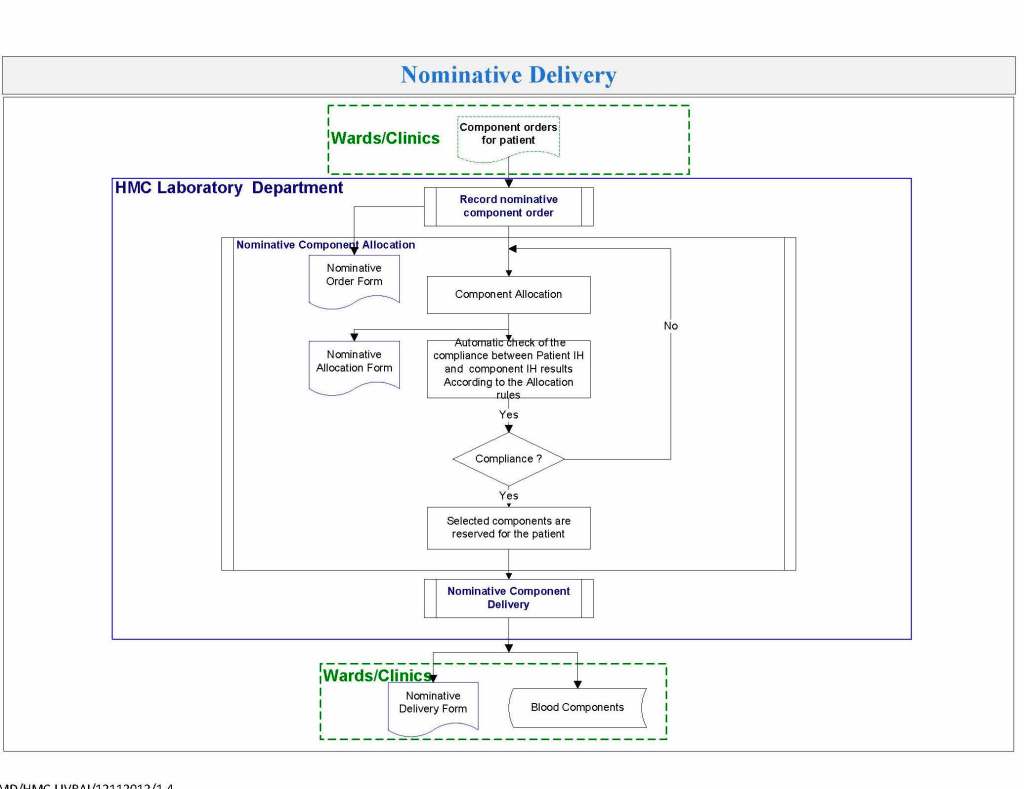

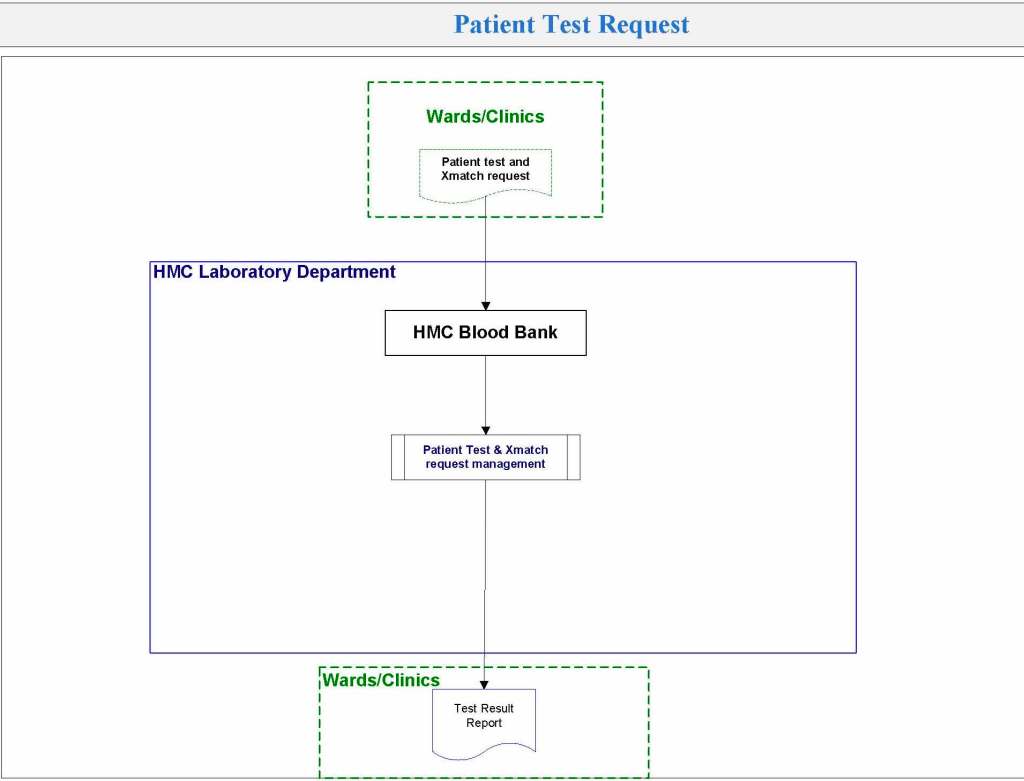

- At least one technologist at each site for inter-depot transfer, component medication (washing, irradiating, aliquoting, reconstituted whole blood), immunohematology testing, component allocation and release

The cost of using these staff? They were paid overtime and were relieved of other duties when working on Super User duties. This was much cheaper than hiring outside consultants who may or may not know our system well enough to perform these tasks.

By having a Super User at each site, I in effect had an immediate local contact person for troubleshooting problems who could work with the technical/nursing staff. We did not rely on the corporate IT department for support and worked directly with the software vendor. Response time was excellent this way.

The following document is a sample document of the assigned Super User duties during a validation.

To Be Continued:

22/6/20